Content Warnings

Cannibalism

Body horror

Memory loss

Depersonalisation

Body shame

Dysphoria

Iriko was hungry.

Iriko was always hungry these days, no matter how much she ate; she could recall a time before the incessant hunger, but the memories had grown dim — a prior era of her life, back when she had possessed arms and legs and a chordate spine. She used to have a stomach, which she could fill by pushing meat and gristle down her throat with a tongue. In quiet moments she fondly recalled the sensation of curling up to sleep with a full belly, to doze and digest alongside companions and friends, in a big pile of slumbering limbs and warm bodies snuggled beneath ragged coats.

None of those things happened anymore. Iriko slept in isolation, in the loneliest places she could find, with her senses wide open.

These days her whole body was a stomach, too large to fill.

Finding good things to eat was also a challenge. Iriko could spend entire days slurping up the black and grey mould which grew all over the city, but grazing on nano-mould always left her feeling slow and dull, like there was less of her than before, even though her physical mass would increase by however much she had ingested. She could easily digest concrete and steel and brick — just melt it with a bit of acid first — but that inevitably made the hunger worse. She could not extract any benefit from inanimate matter, not unless the metal and polymers came from the nano-rich bionics of a living zombie.

Hunting was frustrating. Iriko dared not creep too far inside the graveworm’s kill-zone, where the most vulnerable meat could be found; worm-guard might struggle to destroy her entire body, but they could still diminish her, split her into pieces, scatter her mind. Kinetic force was not much concern, but worm-guard had worse weapons than bullets: phosphor-fire, neuro-chemical disruptors, specially manufactured surface-active agents — all things designed specifically to deal with creatures like her. Iriko was vaguely aware that she’d run afoul of the worm-guard before, but the memories were fuzzy and disjointed. She knew that once she had been much larger and more confident. She had not been ‘Iriko’, but something else, something more coherent and fearsome, something with full memories and a name that was more than the weight of shame. That other, prior, better thing — not Iriko — had penetrated the worm’s safety and eaten many hundreds of revenants. But then she had been burned and cooked and torn into tiny parts, by worm-guard with skins she could not dissolve and weapons she could not deflect. The tiny parts had fled. No others had survived the mistake.

Iriko was one such tiny part.

Iriko was equally terrified of venturing away from the edge of the graveworm’s kill-zone; out there in the true wilds lived things which could eat her as easily as she could eat an unprotected revenant. The most dangerous things in the deeper wilds did not risk coming close enough to catch the worm’s attention, which meant Iriko was safer when she stuck close to a worm — but not too close. On the rare occasions that the true monsters came her way, Iriko grew herself a shell, turned off all her senses, and pretended to be concrete.

Iriko knew that she had made a mistake, or a chain of mistakes, reaching back to before she could remember. She had made decisions about what to become, about how to use the meat and gristle she had pushed down that long-forgotten throat. She had been both cowardly and cruel; now she was trapped between wilds and worm, a girl who was only viable in this narrow margin.

And barely a girl anymore. She didn’t like to think about that. Crying was a waste of resources.

Revenants rarely wandered beyond the edge of the graveworm kill-zone. The ones who did tended to be clever and strong, or well on their way to leaving the zone themselves. If Iriko wanted to eat then she had to be clever and strong as well.

And that’s why she was hunting the tank.

The tank was far from the most interesting thing to happen lately. First a meteor had fallen from the skies and then revenants had swarmed all over the impact site; Iriko had smouldered with frustration that the meteor had fallen just inside the indistinct boundary of the graveworm’s kill-zone, placing all that revenant meat tantalisingly beyond her reach. But some of those revenants had been brave enough or stupid enough to edge just beyond the safety of their worm-guard shepherds. Iriko had herself several successful hunts and some very tasty meals; she was still digesting a particularly large one when the tank turned up.

The tank had come roaring out of the wilds, right past Iriko, and then plunged into the graveworm’s kill-zone, into the middle of what sounded like a huge fight. Iriko had been hanging around in the hopes that some stragglers might retreat in the wrong direction and right into her. But then the tank had returned, intact, which was incredible because it must have fought the worm-guard; then, even more incredibly, a revenant had turned up and knocked on its rear.

That revenant had spooked Iriko very badly; she had looked up at exactly where Iriko was hiding, and then winked, as if she could see right through the concrete and Iriko’s refraction shielding. Iriko hated that, she hated being seen, she hated the knowledge that anything or anyone could witness her as she was now, naked and ugly and shapeless. She had almost pounced from her hiding place to tear the revenant apart — but she was too ashamed for that.

The tank had surprised her again by rumbling off back toward the graveworm kill-zone a second time, with the revenant tucked inside its belly. Round two with the worm-guard? How was that even possible?

Iriko had not expected to see the tank again. Surely it would be destroyed.

But the tank had returned to the edge of the wilds a little while later. It wedged itself in a choice bit of cover, shielded by the collapsed body of an old factory, with a nice clear view down a long empty street. Then the tank had stopped moving for a very long time, all the way through the night and the rainstorm and the morning drizzle.

The tank called itself ‘Pheiri’.

Iriko learned that when she squirted a stream of microwaves, IR comms, and ultrasound echolocation at it. She expected no returns except the topography; the tank was such an interesting shape, with lots of little pits and holes and bumps and knots and curls. She might turn that shape over in her mind for months.

But the tank answered; name! rank! serial number! The tank listed a vast variety of weapons at her and blared warnings in the language of missile locks and ammo-count demonstrations and the chemical composition of warhead payloads; it swivelled the muzzles of auto-cannons to point at the spot from which she had broadcast, and covered her with the firing arcs of half a dozen high explosive missile pods and incendiary projectors. The tank made itself very clear, in no uncertain terms, with no room for misinterpretation.

Iriko tried to ride back up the comms ping with a clutch of viruses, but the tank brandished countermeasures of its own; Iriko had to purge a section of her short-term memory to stop them from spreading through the rest of her flesh.

Then the tank cut the line and stared at her with sensors and weapons, urging her to go away.

But Iriko did not want to go away, not after that. Now she was very interested.

The tank — Pheiri — called itself a ‘him’. That piqued Iriko’s interest further. She’d not met a him in a very long time. Perhaps there were some out in the wilds, zombies or otherwise, but she couldn’t remember ever talking with one.

But her real interest was Pheiri’s hidden meat.

He was carrying zombies in his belly — little throbbing morsels of fresh, rich nanomachines, undigested and moving around. She’d seen that winking zombie get aboard him earlier, and much later she witnessed one of them climb out onto his top deck for a few minutes, a smaller one with high-grade bionic limbs, glowing to her nanomachine-sensitive readouts like a juicy slab of roasted meat.

Other revenants had come to bother Pheiri a few times during the night, but he didn’t capture those ones and tuck them away inside his belly-pouch: he shot at them with some of his smaller weapons. Most of them ran away to regroup, but some of them died. Pheiri did not move up the street to consume the corpses, but just left the kills uncontested.

The corpses were still there when dawn came, all split apart and wet and red. Iriko wanted to eat them, but in order to reach the dead revenants she would have to expose herself to the open street, with Pheiri at one end. He would see her, her real body, even through her refractive shielding. He would see her in the visible light spectrum.

She wasn’t worried that Pheiri might shoot at her; that was just silly talk, boys liked to do that.

No — she was ashamed of what she’d become. She did not want to show herself.

Iriko slid and slipped and slithered down to ground level anyway, just beyond Pheiri’s sight. First she tried to make herself look like concrete and creep out into the street, but Pheiri turned all his sensors toward her anyway. He saw right through the disguise. She retreated and tried something else: she extended a small part of herself and tried to make it look like a revenant, with arms and legs and a head, with curves in the right places, and long black hair, just like she used to have. She dressed it in a pink kimono and put sandals on its feet. She turned it around several times and thought it was very pretty.

But when she stuck it out into the street and walked it over toward the corpses, she started to feel horrible and fake and wrong. The puppet didn’t even look like she had done in life — she couldn’t remember clearly enough. The kimono was all fleshy and rippling, the hair looked like black straw, and she couldn’t make hands anymore and the lips didn’t work and there were no teeth and—

Iriko dissolved the puppet into a pseudopod and pulled it back into her main body, ashamed that she’d shown something so pathetic to Pheiri. She attempted a couple more tricks, but after the stunt with the puppet she just wanted to grow eyeballs and cry to herself in the dark.

Eventually she crawled out into the street. She didn’t even bother with her refractive armour. She slumped up to the corpses and covered them with her body, dissolving meat and organs and bionics and bones. She made no effort to hide from Pheiri. She stared at him, daring him to say something rude.

Iriko was huge and formless, maybe two thirds Pheiri’s size. Her ‘skin’ was the colour of oil on water. Faceless and limbless and semi-transparent. She knew what she was.

Pheiri stared. Pheiri said nothing. Pheiri let her eat, and did not judge.

When she slid back into the ruined buildings, Iriko started to think that maybe Pheiri was a nice boy.

But the scraps of meat were not enough; no amount of revenant meat ever was. Iriko circled the area a few times, worming her way through the tops of the tightly packed buildings, squirming down stairwells, pushing her protoplasmic body through air vents and duct systems. Eventually she located more revenants similar to the ones who had bothered Pheiri in the night — she recognised the skull symbol on their armour, but she couldn’t recall what that meant. They were hiding in a long, low, lightless building, a little way toward the graveworm’s kill zone. They were also heavily armed and highly organised; they had some kind of big gun on a machine. Iriko tried to sneak up on them, but they spotted her with cybernetic senses and sent chemical fires to eat at her flesh.

She gave up on that prey and slipped back toward Pheiri; she returned to a spot inside a block of apartments, about ten floors up, where she could look down at Pheiri in the street below.

She was still hungry. She was always hungry. And Pheiri had been nice. He’d let her eat the kills. That had never happened before.

Iriko squirted a fresh beam of encrypted data down toward Pheiri, virus-free and unscrambled into plain language.

「pheiri pheiri eat-share? hungry so hungry need meat lots inside lots lots more than needed? eat-share share-eat. show where more meat is waiting, offer meat offer share. please hungry small so small. share small? only small. only small. promise please please.」

Pheiri ignored the beam, rejected handshake, and replied with a blurt of wide-beam comms:

「NEGATIVE cease communications remove self 500 meters rear」

He backed up the rejection by targeting her new position with a set of rack-mounted missiles, then broadcast the chemical formula for several nasty forms of incendiary weapon and anti-surfactant, ones that even Iriko could not easily metabolise.

Iriko wanted to huff and put her hands on her hips; she thought Pheiri was a nice boy! But he was rude, and a boor, and ungentlemanly. She did not have lungs or hands or hips anymore, but she toyed with the notion of extruding a mouth so she could pout.

She sent another beam: 「talk just talk no weapons talk about meat want more you have meat give me your meat please want please. iriko iriko is me namekujin iriko please hello iriko please say」

Pheiri replied: 「NEGATIVE final warning remove self 500 meters rear open fire 15 seconds」

「so much meat! all yours! all yours! you don’t need you’re metal and plastic and a nuclear reactor why can’t I have a nuclear reactor it’s not my fault! not my fault, want meat want what you—」

Handshake crackled back up the tight-beam. Something else replied to Iriko’s tantrum, something inside Pheiri. An audio signal unspooled inside Iriko’s body.

「“We let you have the Death’s Heads, zombie. Go away or Pheiri will turn you into paste. We don’t have time to fight you right now, we do not want to engage. Do you understand? We’ll kill you if we have to. Go on, shoo.”」

The tight-beam connection cut out.

Iriko remained motionless in the tower stairwell for sixty whole seconds, long past Pheiri’s deadline. Then she slowly went limp, her bulk filling the entire stairwell landing, spilling down the stairs and up the walls and across the ceiling. She stared and stared and stared. She wanted to sob. She almost grew a throat for that express purpose.

Pheiri wasn’t trapping zombies to eat them later: he was protecting them.

Iriko let out a whine. She was so embarrassed. They’d all seen her!

Iriko pulled herself together and hurried up the stairwell. She slid through the dark interior of the apartments, over mounds of rubble and drifts of dust, ignoring the sweet temptation of mould-mats and walls caked with grey rot. She wormed her way through the top of the building, then found a sealed door for roof access. She melted through the hinges, pushed the door aside, and slid out onto the roof.

Iriko did not like exposing her body to the open sky, even armoured in refractive mail; she told herself this was because she felt vulnerable, because something might attack her from above. But that was a lie. She hated the sky. She hated the endless black clouds and the dead sun like an ember in a cold fireplace. She hated the shame of what she had become, the shape of her expanded form. When she was down in the dark and hidden below the buildings, she could pretend she was anything at all, wearing anything she liked.

But she was angry, and mortified, and embarrassed. Enough to go out onto a rooftop.

And she was hungry.

She slid to the edge of the roof. Her body soaked into the concrete, tendrils and surfaces exploring the cracks, sucking at tiny pools of moisture, and greedily digesting scraps of black mould. She peered over the concrete lip, down at Pheiri.

He stared back up at her with dozens of sensor systems. He knew exactly where she was.

She wanted to stick her tongue out at him. Rude!

Iriko could form long-range weapons if she needed to, but her body was limited to squirting chemicals or ejecting hardened darts. Neither of those would penetrate Pheiri; none of her formulas would burn or melt his suit of armour. Pheiri had not transmitted the molecular composition of his shell, and Iriko suspected the armour itself was a clever trick. It looked exactly like bone, but her sensors told her otherwise: super-dense, ultra-light, and self-regrowing, like the bone would keep expanding even when separated from blood and meat. She did not want to risk getting a piece of that inside her body.

She considered jumping from the tower and forming herself into a hardened spear, pointed at Pheiri; she’d used that trick once before to finish off something from the deeper wilds which had not been fooled into thinking she was a lump of concrete. Iriko was perhaps half or two thirds Pheiri’s size, so she could probably overwhelm him with sheer weight in a first strike. But would her spear-tip be hard enough? She experimented with copying that special super-dense bone he was wearing; she extruded a point and kept trying to harden it in new ways, but she couldn’t get past diamond.

This was so unfair! She wanted to slink away into the dark and pretend this had never happened, but the hunger was terrible and Pheiri had so much meat inside.

She peered back over the ledge and made a face at Pheiri. She hated him now. Why wouldn’t he share?

「fuckboi shit-face guilt trip fuck you fuck you fuck you!」

Pheiri replied with a blurt of pure static. Iriko flinched and backed up.

She retreated to the middle of the roof. She felt very alone and very bitter, which she had not felt in a long time. She wanted to cry, but making eyeballs and producing tears would be a waste of energy and water. Instead she found a place where the roof had collapsed inward. She picked up a huge piece of loose concrete, twenty feet across. She hefted it with a dozen pseudopods, tested the weight, and started to calculate the trajectory to hurl it onto Pheiri’s stupid head. His point defence systems would undoubtedly blast the concrete apart, but Iriko didn’t care, she wanted him to know that she hated him now. She was going to throw things at him until he moved and—

Crack-crack!

Two bullets hit Iriko’s right flank.

The first bullet was unremarkable lead; Iriko melted and digested the round instantly. But the second bullet contained a neurotransmission blocker laced into the metal, released as she began to digest the material — pointless against a zombie, almost useless against her in such a small quantity, but just clever enough to get her attention.

She traced the bullets’ trajectory; they had come from two rooftops away, amid a nest of rubble, all crumbly concrete and rusted steel bars. But there was nothing there except ambient nanomachines and inert material. Nothing scuttled away or slipped into the cracks. Where was the shooter? And why try to get her attention like that and then hide?

Iriko flowered her senses open, blanketing that distant rooftop with sheets of microwave radiation and radar returns. She scanned surfaces and topography to find anything out of the ordinary. She extended actual eyeballs on stalks, human-like and insect-like and some that she had invented herself, smearing her sight across the visual range and beyond, into infra-red and ultraviolet. She blasted the area with echolocation pings and odd-one-out predictive mapping equations, and—

Radio contact crackled across the surface of her skin, short-range, point-blank.

「Here. Look here. See me.」

A spindly, mushroom-pale hand emerged from inside a bundle of black rags. The hand waved to Iriko.

The rags had not been there before, or they had appeared to be something else, masked by irrelevance. The pale hand was joined by two more arms, a moon-like pale face half wrapped in metal, and the massive barrel of a sniper rifle.

A revenant, a little one. Beyond the graveworm line, just like the others. No skull on her clothes or flesh.

But this one was out in the open, alone, exposed.

Iriko gently lowered the chunk of concrete. She moved very slowly, so as not to alarm the revenant. She did not want it to run. She started to creep across the rooftop, toward the opposite edge. There was one building between her and the pale many-armed revenant with the sniper rifle. She could make that leap with ease; she began to gather muscular power and tension in the underside of her body.

Radio contact crackled again. The revenant said: 「Stop moving. I’ve got worse than nerve agents. Give it up.」

Iriko stopped. She replied on the same point-blank wavelength: 「out open out alone? going to get eaten. going to eat you. you run but you’re smaller and slower and you can’t stop every part of me lie down and sit down and gun down and let me come let me come let me—」

「Stop. Let’s talk like people. You’re still a person in there, right? We’re not that far from the graveworm safe zone. I can still run. Then you get to meet worm-guard. But I have a deal for you. Mutually beneficial arrangement. How would you like to eat some zombies for me?」

「eat you eat you eat you eat you eat you you you you you you you」

Across the gap, Iriko saw the revenant sigh. 「Too hungry to wait, huh? Fine. I’ll lead you there. But you don’t get any cover. You better be as quick as you look, or the Death Cult are gonna fry you.」

The revenant stood up suddenly and made her sniper rifle vanish inside her black robes. She was very tall and very spindly; Iriko sensed reactors powering up inside the revenant’s body, shedding stealth for strength and speed. She whipped around on the spot, black robes flying out behind her as she turned and scurried back across the ruined rooftop.

Iriko bunched her body like a spring and exploded from her own roof; the impact cracked the concrete behind her as she shot into the air.

She narrowed herself into an aerodynamic dart and slammed into the debris two rooftops away. Dust and shrapnel and bits of metal exploded in every direction. She unfolded herself like a net, shoving the concrete and rebar aside with all her strength, hot on the scent of fresh meat and healthy reactor spoor.

A flutter of black robe slipped around the frame of a roof-access door. Iriko gave chase; she ripped the door frame out and flung it aside and squeezed her body through the opening, rushing into the shadowy interior, sliding herself across every surface, groping for an ankle or a piece of black robe or a strand of hair.

She needn’t have bothered.

The pale, spindly revenant was standing with her back against a railing, her body relaxed and loose, less than ten feet away; behind her was the drop straight down the middle of the stairwell.

Iriko reached for her.

The revenant flicked off a salute, kicked off the floor, and rolled herself backward over the railing. She dropped right down the empty centre of the stairwell, head first. Iriko was so surprised that for two precious seconds she did not follow; she just peered down the stairwell, watching the falling comet of black rag and mushroom-pale flesh.

Iriko leapt.

The revenant landed first, twisting herself like a cat, springy limbs absorbing the shock; she bounced from a standing start and shot through a set of doors without even pausing to look. Iriko landed a second later and splattered all over the inside of the stairwell’s ground floor. She had to spend five seconds pulling herself back together and making sure she didn’t leave any parts behind. Then she slammed through the doors as well. She was losing her temper.

Down a long dark corridor, the ruddy daylight flickering through the windows; across an open court with markings for a ball game, dodging in out and between the quiet husks of dead machines; through the frontage of a building that had once served food, the trays and tables and bins now empty of anything but dust. The strange spindly revenant ran just a little too fast for Iriko, always a few meters beyond reach, always with some new trick to duck or jink or dive out of the way. Iriko shattered walls and tossed furniture aside and chewed at the floor in her frustration.

Eventually the revenant crossed an open stretch of street and plunged into a long, low, lightless building. Iriko powered after her, slamming doors off their hinges, ignoring the switchback corners of the corridor, and smashing straight through a concrete wall.

Iriko recognised the building a moment too late; this was the place the well-armed, extra-clever, skull-wearing zombies were staging their weapon with which to attack Pheiri. When she’d tried to creep upon them from above, they’d spotted her instantly and turned their weapons upon her. And she had just shattered the concrete wall which led to their big chamber.

The bulk of her body had too much momentum to stop; she exploded through the wall and slammed down into a big room with hoops at either end and markings all over the floor. She started to rear up to pull herself back, to escape the inevitable chemical repellents and flame weapons and protective sprays, and—

And all the skull-wearing revenants were looking away from her.

Some of them had been knocked down by the wall she’d shattered. All the others were exchanging small arms fire with a pale, spindly, black-wrapped figure up on a gantry. They were shouting insults at the pale revenant, shouting orders at each other — and then turning in shock, their faces covered in concrete dust and blood, to stare at the multi-ton blob monster which had ambushed them from a new and unexpected direction.

Iriko fell upon them, as quickly as she could.

When she was done sucking flesh from bones, and breaking bones to suck out marrow, and sucking bones deep inside herself to be digested, she felt a radio broadcast crackle over her skin once again.

The pale, spindly, clever revenant up on the gantry said: 「Good work. Said I would lead you to meat.」

Iriko replied: 「not for you not you not for you」

「Hmm? Not for me?」

「pheiri pheiri. big gun make him scared make him rude and bad boy bad for me bad for him. bad zombies get eaten so no pheiri rudeness bad」

Up on the gantry the revenant produced her sniper rifle again and looked through the scope, at the big mess Iriko had made. 「Oh, the lance. Mm, whatever you say. That tank is more than capable of dealing with low grade AT weaponry.」

Iriko picked up a piece of the big gun — she’d broken it while she’d been eating — and waved it at the woman on the gantry. She tried to make a rude gesture, but she didn’t have the fingers to make it work.

The woman laughed anyway, a muffled metallic chuckle from behind a steel half-mask painted with big black teeth. 「No offence. Now, do we have a deal, or are you going to chase me again?」

「deal deal? deal eat deal?」

「More meat. For you. If you want it. All you need to do is be in the right spot and wait. My name is Serin. Does that help? What’s yours?」

「iriko iriko iriko. not me not anyway anymore namekujin joke bad bad joke because I’m iriko」

The woman leaned against the gantry. Her eyes looked sad. 「That’s not a name. That’s just what you’ve become. Am I right?」

「eat you」

「You’re welcome to try. Pheiri might not like that.」

Iriko pulled herself as small as she could and made her refractive armour the same colour as the floor. 「know pheiri know pheiri say hello say from me me me not here not from me not pretend say?」

The woman chuckled again. 「I can pass on a message. From a secret admirer. If we have a deal. Do we have a deal, Iriko?」

「eat」

「I’ll take that as a yes. Follow me.」

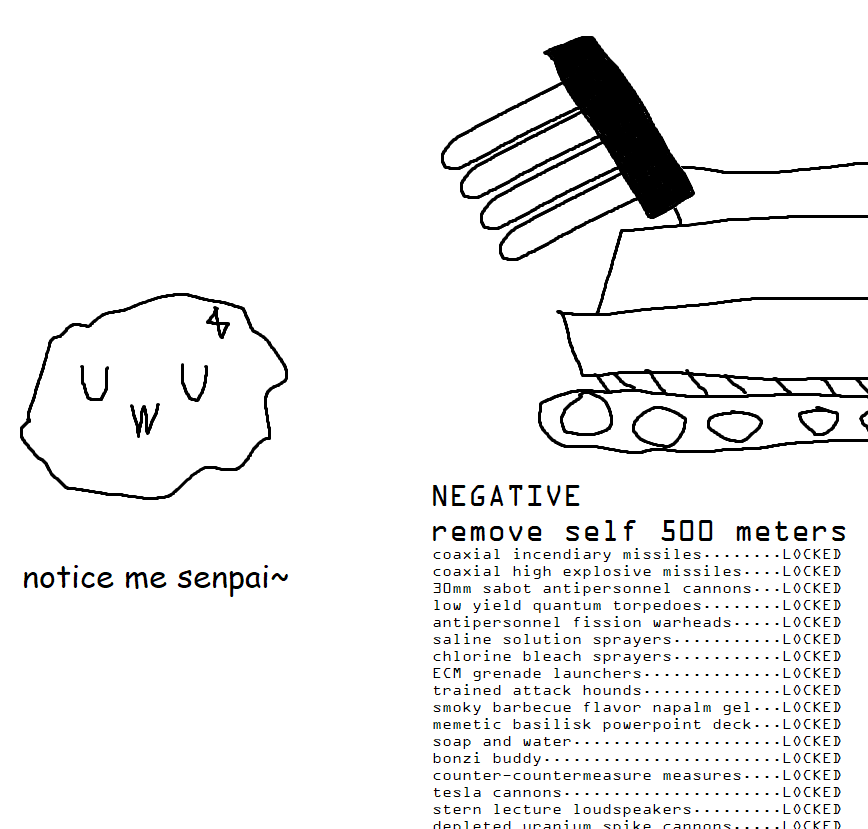

A 100% accurate depiction of the events of the Interlude chapter.

(The image above is by ray, over on the discord! It had me howling with laughter, and I just had to share it with more readers. Thank you so much for letting me share it here, ray!)

Surprise, it’s an interlude! A squishy, squirmy, slimy, sticky, slippery interlude. Slug girls. Woo. I wasn’t actually sure if this interlude was going to come here, or later in the story, but this ended up as the perfect moment to explore a bit beyond the boundaries of the graveworm safe zone. I’m sure we’ll see more of Iriko (and Serin, again), in the future. Next chapter we’re onto arc 9 for real.

If you want more Necroepilogos right away, there is a tier for it on my patreon:

Right now this only offers a single chapter ahead, about 4.5k words. Feel free to wait until there’s more story! I’m focusing on trying to push this ahead for now, seeing if I can make more time in my writing schedule to get an extra chapter or two out. I’ll keep doing my best!

There’s also a TopWebFiction entry! Voting makes the story go up in the rankings, which helps more people see it! This only takes a couple of seconds, and it really helps the story.

And as always, thank you so much for reading my little story! I dearly hope you are enjoying Necroepilogos, and these strange places we’re going, as much as I am enjoying writing about them. Until next chapter!