Content Warnings

Grief/(implied) loss of partner/(implied) loss of headmate

Howl was gone.

Elpida felt her sister’s absence like the bleeding socket of a shattered tooth, or the phantom pain of a severed limb, or the fading warmth of abandoned bedsheets. She knew that Howl was not merely asleep, unconscious, or quiet, in the same manner she knew the position of her own legs and arms. This absence was a raw and open wound. Something had been torn away from Elpida’s mind, something she had not known she possessed, not until it was gone.

“Howl?!”

Her shout filled Pheiri’s crew compartment.

Her comrades could not spare further shock or alarm — everyone was busy struggling to retain their balance, stowing weapons and equipment, dripping grey mud from saturated clothes, lurching and reeling with wide-eyed panic and helpless fear.

Pheiri was accelerating, tracks crunching, engine roaring, weapon emplacements pounding out a chorus of bullets and missiles beyond the hull; he was still fighting the ball-shaped rotor-craft, despite the damage to the gigantic airship. The crew compartment juddered and jerked as Pheiri skidded and swerved, tossing everyone from side to side as he took evasive action, speeding through the streets of the corpse-city. He was likely trying to place himself beyond the blast radius of a second atomic detonation; his nano-composite bone armour had protected his insides and his crew, but even he had limits.

Elpida held fast to a piece of wall-rib and screamed at the silence inside her own head.

Howl?! Where did you go? Answer me! Howl!

No reply. Howl was not there. Howl was gone.

Elpida pinpointed the exact moment she had lost track of her sister — lost Howl a second time, all over again. It was happening again!

Howl had gone silent during the flight across the muddy crater, seconds before Arcadia’s Rampart had reared up and blossomed into a whirling tower of flesh and bone. Howl had nothing to say about the combat frame’s terrifying and beautiful transformation; Elpida had assumed that Howl was focused on survival and extraction, silently urging Elpida onward, keeping her steady, giving her purpose. Elpida had sent a distress call to Pheiri, then concentrated on keeping the small group together and moving; Kagami couldn’t run, Vicky was terrified, so they both needed help. Elpida had expected Howl to cheer when Pheiri had burst into the crater and hammered a rotor-craft out of the sky; she had expected an awestruck gasp when Arcadia’s Rampart had landed a railgun strike on the golden diamond, or when the crossbeam of the vast airship had detonated with the force of an atomic blast.

Not all Howl’s vocalisations were clear, not all her comments were coherent, not all her emotions were fully expressed — but they were always present in the back of Elpida’s head. Elpida had not yet grown used to this new dual-minded way of being, this passenger inside her skull, but the sudden absence of her clade-sister made her realise just how much of Howl’s input was non-verbal.

She had lost her second in command, the angel on her shoulder, her devil’s advocate. All over again.

Had Howl departed on purpose? Had all her support been nothing more than the surface bait of a cruel manipulation?

Howl, don’t, don’t leave me, don’t go now. I can’t do this alone, I can’t—

Pheiri swerved a hard left, tossing the contents of the crew compartment to one side. Tiny projectiles or debris pattered off his hull like a rain of steel.

Hafina was halfway to the infirmary, dripping liquid mud from her cloak and armour, cradling Kagami in her arms; she braced herself against the wall and floor, rocking with the sudden motion. The others didn’t fare so well. Atyle was already sprawled on the floor, her skin covered in blisters, sliding to one side as Pheiri swerved. Ilyusha and Amina went tumbling together, slamming into a wall with a hiss and a yowl. Ilyusha caught Amina and held her tight, to spare her the worst of the impact. Vicky flew out of her seat, eyes wide, arms wind-milling for a handhold.

Elpida hooked Vicky around the waist before she could crash into the wall. Pheiri slewed to the other side, tossing everybody back again. Vicky yelped, clinging to Elpida’s arms. Ilyusha spat a curse. Amina screamed.

Howl! Last chance. If this is a joke, stop, right now. If you’re in trouble, communicate with me however you can. If you’re not here … if you’re not … not here …

Elpida knew she would be dead without Howl.

She was already dead, already a zombie — but without Howl, Elpida would have died again, and not in a temporary manner, not to be resurrected by the lingering power of her nanomachine biology. Without Howl’s relentless support, Elpida would not have escaped from captivity, would not have escaped the Death’s Heads and Yola and their sick designs on her. Without Howl to pull her out of defeat and despair, Elpida would have lingered in the false darkness of dreams and delusion. Howl had forced Elpida to her feet and made her keep fighting, even when her body had screamed to stop. Without Howl, Elpida’s companions would not have their Commander, Pheiri would not have found his Telokopolan pilot, and Thirteen would not have reconciled with her combat frame. Without Howl they would all be dead, to be resurrected again in ten or fifty or a hundred years, separated and broken.

Howl, please. I can’t do this alone.

Had Howl betrayed her? Was ‘Howl’ even Howl?

Elpida had simply accepted the reality of Howl’s voice, the support and reassurance of her sister back at her side, the miraculous resurrection of one she wished for so dearly. But Howl had not explained how she had come to exist, or how she had come to be riding along inside Elpida’s head. Howl had explained nothing.

Elpida’s mind raced to construct a working hypothesis. She had three options: Howl had either departed on purpose, or been intentionally taken away, or been left behind by accident. There was a fourth option, of course — Howl may be dead — but Elpida discarded that as useless. She couldn’t act on that. Howl had germinated, or been planted, or moved into Elpida’s mind when she’d been unconscious, chained to the Death’s Heads’ surgical table, dying of a gut wound, at the exact moment Elpida had needed her most. Howl could have been lying dormant since Elpida’s resurrection in the tomb, or she may have arrived later.

Her origin did not matter. What mattered was that she could leave.

Why now?

Elpida made two educated guesses: either the golden diamond in the sky — central’s ‘physical asset’ — had ripped Howl out of Elpida’s mind; or Howl had departed on purpose, to give Thirteen the last push into transformation.

Both of those meant Howl might be trying to return home.

Home? Home was Telokopolis. Home was Elpida.

Elpida was inside Pheiri’s hull, sheltered from most electromagnetic interference. And Howl was out there, in the whipping winds and fallout and radiation of an atomic detonation.

Or she had betrayed Elpida, because she was never Howl in the first place.

That was not a risk Elpida could take.

She chose trust.

Okay, Howl, I’m coming to find you and pick you up. Hold on.

Elpida slammed Vicky back down into her seat on one of the crew compartment benches. She yanked at the belts and webbing and got Vicky strapped in, despite the slippery grey mud all over Vicky’s clothes and Elpida’s hands.

Vicky stammered: “E-Elpida, Elpida, Kaga is—”

Elpida struggled to keep her balance as Pheiri swerved again. “Vicky, you stay there, stay put, stay strapped in. Pheiri needs to move fast. We can help him by protecting ourselves. That’s an order. Stay there.”

“Kaga—”

“Haf’s got her. The wound is shallow. She’ll be fine. Stay there.”

Elpida did not wait for acknowledgement. She swung away from Vicky to see to the others.

Ilyusha was already bundling Amina into a seat and tugging the straps across her chest. Ilyusha’s claws gave her better handholds on Pheiri’s innards. Amina was crying and heaving with panic, cradling one badly burned hand; she had been briefly exposed when the blast wave had hit.

Elpida hurried past them. “Illy, Amina, you two stay here as well, stay strapped in, look after each other.”

Amina said: “But Pheiri—”

Elpida caught a bulkhead rib and twisted round to look Amina in the eye. “Pheiri is trying to save us. We have to help him by staying safe. Your job is to stay safe. Do you understand?”

Amina nodded, tears streaming down her face. Pheiri swerved again; the movement was punctuated by the thump-thump crack-crack of his guns — not the small point-defence weaponry, but the big weapons, the autocannons and missile pods. Explosions blossomed beyond the hull, buffeting the crew compartment with noise and fury. The firepower shook Pheiri’s insides, drawing a scream from Amina’s throat and throwing Elpida backwards.

Ilyusha reached out and bunched a clawed fist in Elpida’s coat, catching her before she could crack her head on the metal wall.

Illy bared her teeth. “What about you!?”

Elpida grabbed Ilyusha’s hand and squeezed hard. “Howl’s gone. We left her behind. I have to find her.”

Ilyusha let go, grimacing through clenched teeth. She nodded and threw herself down into the seat next to Amina. Clawed hands pulled straps and webbing over her body. Clawed feet gripped the decking. Pheiri fired again; the recoil made the crew compartment shudder and shake. Elpida braced her hands against the wall.

“Illy, where’s Pira and Ooni?”

Ilyusha jerked her head at the corridor to the control cockpit. “Up front!”

Elpida scrambled forward. She grabbed the hatch to the infirmary and stuck her head through.

Hafina and Melyn had worked fast; Kagami was laid out and strapped down on one of the infirmary slab-beds. Her coat was peeled away from her right shoulder, revealing a burned, pulped mass of flesh on her upper right arm. Blood was pooling on the floor, reduced to a trickle by an emergency tourniquet and bandage. She’d taken a shrapnel wound during the flight across the crater — a lucky shard of metal had slipped between the halves of her coat and sliced open her arm. The wound looked much worse than it was; Elpida had taken worse in life and come away with nothing more than a short visit to medical.

Kagami snapped as soon as she saw Elpida. “Fucking hell! Fuck me!” Her eyes were wide, pupils dilated with pain and fear. “Commander, Commander, we have to get out of here!” She looked up at the ceiling and the walls, eyes jerking every which way. “Go faster, damn you! Remember me?! Remember me from the fucking radio!? Drive faster! Commander, make this thing go faster!”

Melyn was clamped to one of the fold out chairs — legs braced beneath the seat, arms gripping the sides, her tiny, pixie-like frame bouncing with every rut and hole in Pheiri’s path. Hafina hadn’t bothered to sit, perhaps conscious of her mud-soaked clothes; she used her height and her many limbs to brace herself against the ceiling and walls, riding the swaying like a gyroscope.

Elpida said: “You two have Kaga in good hands?”

Hafina grinned. “Lots of hands.”

“Don’t try to treat her until we’re secure. Stay strapped in. Be safe, both of you.”

Melyn rattled off a reply. “Yes yes yes, yes yes.”

Elpida lurched back into the crew compartment. Atyle was still sprawled on the floor, making no effort to pull herself up into a seat; that seemed to be a successful strategy so far, keeping her centre of gravity low. The exposed skin on her face and hands was red and raw, starting to blister and peel; she’d been standing on top of Pheiri when the first part of the blast wave had rolled over the crawler. It was a miracle she hadn’t been blown off Pheiri’s hull or had her flesh melted to her bones; either the distance or Ilyusha’s quick thinking had saved her. Elpida and the others had been sheltered by Pheiri’s armour, just inside the hatch when the detonation had hit. They’d reached him just in time.

Atyle was smiling at the ceiling, lost in private visions, one hand pawing at the air. Her biological eye was milky and blank with light damage. Her peat-green augmetic was wide and whirring.

Elpida dragged Atyle off the floor and strapped her into one of the bench seats, then grabbed her face and stared into Atyle’s bionic eye.

“Atyle. Atyle, concentrate. I need you, right now. I need your sight.”

Atyle blinked. Suddenly she was lucid. She slurred through burned lips. “Warrior?”

“If you really can see into brains, I need you to confirm something for me. Howl is gone. I don’t understand why. Is she still inside me?”

Atyle paused, then said: “You are alone, warrior. The other one is nowhere.”

Elpida’s heart lurched. She nodded. “Thank you. Stay here, stay strapped in. We’ll tend to those burns later.”

“Tend? Nay, warrior, they are proof of a divine hand.”

Elpida straightened up. Pheiri was accelerating straight ahead, skidding over rubble and rock, bouncing and slewing. Elpida gripped the rib of an interior wall and stripped off her mud-soaked cloak, dropping it to the floor. She unhooked her submachine gun and tossed it onto the bench. She pulled off her armoured coat, stamped out of her waterlogged boots, and pushed her trousers down her legs. She didn’t care about the cold or the discomfort; she needed to move fast. If her hypothesis was right then Howl might be trying to return home right then, trapped beyond Pheiri’s hull, alone.

Elpida ducked into the connecting corridor and hurried for the control cockpit. She banged her elbows and skinned her knees in the tight confines. She cracked her head off low-hanging equipment and smacked her hips into chairs and control panels. Her gut wound was still not healed; it complained and ached as she doubled-up, sending spikes of pain deep into her abdomen. She crawled most of the way, past the access hatch and the bulge of armour over Pheiri’s brain. When she passed beneath the turret-ladder she looked up into the gloom, at the gleaming hint of the MMI-uplink helmet.

“Hold on, Howl,” she whispered.

She burst into the control cockpit and hauled herself upright. She clung to the back of a chair as Pheiri lurched to the left; the massive crawler entered a long, curved, skidding motion, bringing his front around, letting his rear end carry him with sheer momentum and weight. Through the tiny steel-glass window in the cockpit Elpida saw snatches of building and soot-dark sky and a toxic golden glow in the air, all whirling as Pheiri struggled not to spin out. She heard Pheiri’s tracks biting and clawing at concrete and asphalt as he pulled out of the slide.

From far behind, far beyond Pheiri’s hull, Elpida heard a second unmistakable crack-thump of earth-shattering railgun discharge. She braced for a second blast wave.

But this time there was no atomic detonation.

A miss?

She had no idea how the fight was progressing. But she couldn’t help Arcadia’s Rampart and Thirteen. Not without a combat frame of her own.

Or could she?

Two wicks with one flame, wasn’t that how the old saying went? If one of those wicks was Howl and the other was Thirteen, perhaps Elpida had a way to keep both of them burning.

Pheiri pulled out of his skid with an almighty lurch, throwing everything forward. Elpida would have gone flying if she hadn’t dug her fingernails into the burst stuffing of the chair. She clawed her way to the front of the control cockpit, braced for more of Pheiri’s evasive manoeuvres.

Pira and Ooni were strapped into two of the forward seats. Pira still looked like absolute hell, like a corpse lifted from the mortuary slab and injected with adrenaline. Ooni was wide-eyed with terror, lips peeled back, hands shaking as she gripped the armrests. Both of them were staring at one of Pheiri’s little screens. Elpida wiped her mud-drenched hair out of her face.

Pira looked up, hard-eyed. She snapped: “You lost somebody.” It wasn’t a question; she’d read it on Elpida’s face.

Elpida nodded. “Howl.”

Pira squinted. “What? How? She’s in your head.”

“I don’t understand. But we’re going to get her back. I need access to Pheiri’s comms systems. Pheiri? Pheiri, can you spare enough attention to speak with me? We need to—”

Ooni sobbed through clenched teeth. “Commander! Commander, we’re going to—”

Elpida put a hand on Ooni’s shoulder and squeezed hard. Ooni winced. “Nobody dies. Nobody gets left behind. Never again. Hold on. Close your eyes if you have to. There’s no shame in that.”

“But!”

Ooni pointed at the screen she and Pira were watching.

The screen showed a false-colour exterior view of the battle back in the crater, with the buildings and obstructions cut away, the picture constructed by sensor readouts and radar information. The false colour was outlined in greens and blacks, flickering with heavy static, harsh on the eyes.

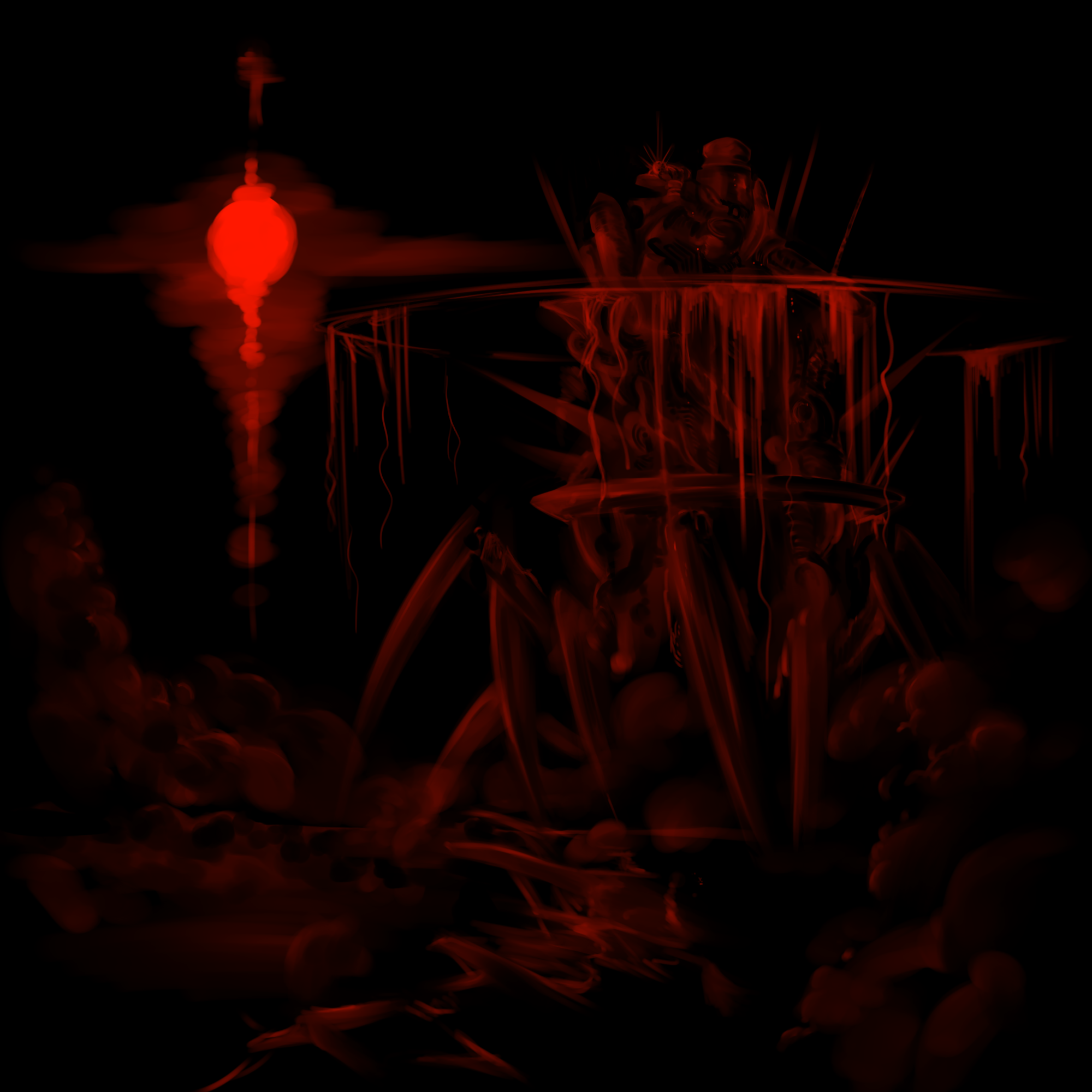

Arcadia’s Rampart — or the angel of flesh it had become — had scored a single titanic hit on the giant golden diamond, shattering one of the crossbeams with a railgun slug. Elpida had witnessed that strike in the final second before she’d bundled everybody on board Pheiri and slammed the ramp shut.

Now the diamond was listing to one side, reeling and rocking, bleeding a million gallons of golden fluid into the crater; the fluid superheated the grey mud where it fell, turning the sucking mire into a boiling cauldron of toxic gold. The vast airship lashed out in all directions with gigantic feelers of artificial gravity — those were invisible to the naked eye, but Pheiri highlighted them with grey-scale overlays and measurements. The machine’s tantrum was smashing buildings to dust, pulverising metal into explosions of splinters, throwing up waves of boiling grey mud, and even knocking many of its own auxiliary craft out of the sky. The edges of the crater were already blackened and blasted by the atomics, buildings crumbling and earth charred, but the machine’s tantrum would leave nothing standing.

Arcadia’s Rampart stood amid the onslaught, golden toxins streaming off its armour and burning into its flesh. The combat frame — so changed now, into a thing of blossoming muscle and flower-like protrusions — was scuttling to retain its footing amid the shifting mud and collapsing ground. It pounded the golden diamond with every weapon it had; the railgun was once again concealed, withdrawn, perhaps charging magnetic coils for a third shot.

Elpida had not begun to process the combat frame’s transformation, or what Thirteen had told her, or what any of that meant. None of that mattered right then. Elpida did not care. A comrade was in battle.

“You can do it,” Elpida hissed. “Come on, Thirteen. Get out of there. Get out of there.”

“It can’t!” Ooni wailed. “It’s trapped!”

Ooni was correct.

The diamond was thrashing and writhing like a cornered animal. Perhaps it was dying. But Arcadia’s Rampart was unable to withdraw in good order. For all the transcendent beauty of the flesh-and-bone change, even an uncaged combat frame was not invincible. The exposed flesh was blackening, the armour buckling, the limbs bowing under repeated blows. In minutes Arcadia’s Rampart would fall to the onslaught of gravitic assault, or get trapped in the sucking whirlpool of gold-baked mud, or melt under the torrent of ichor and chemical damage and radiation.

Elpida said quickly: “Is she talking to us?”

Pira squinted. “She?”

“Thirteen, the pilot. Any broadcasts?”

One of Pheiri’s little black screens flashed to life, scrolling with green text.

>

///message log buffer 73/73 direct contact attempt unknown

///re-designate: “Thirteen”

///73/73 direct contact attempt corrupted datastream rejected

>

Elpida nodded. “She’s trying to contact us but the data is corrupted. Understood. That’s to be expected, she’s changed too far and she’s in the middle of the fight of her life. We’ll have to re-establish communication protocols later. Pheiri, we’re going back to help her.”

Ooni spluttered: “What?! No! Back into that? No, no!

Pira snapped: “Nobody gets left behind, Ooni. You heard the Commander. Nobody get left behind. Shut your mouth.”

Ooni squeaked.

Pheiri refreshed the green text.

>

///local volume radiological hazard class alpha

///local volume biological hazard class alpha

///local volume chemical hazard class alpha

///local volume nanomechanical hazard class alpha alpha plus

///local volume signals hazard class unregistered

>

Elpida said: “I know. Pheiri, listen to me very carefully. Howl is missing — the girl inside my head. That means she was somehow independent of me. A piece of data. I don’t know. She may be trying to get back to me, back home, through all that stuff out there. Signals can’t penetrate your hull, not unless you invite them, so I need you to listen for Howl trying to get home. But I don’t know if you’ll recognise her without me.”

>

///datastream capture protocol engaged

///data entity buffer WARNING DO NOT WRITE MEMORY

///internal firewall integrity check . . . passed

///passthrough connection request nanomachine conglomeration ‘Elpida’

///waiting …

///waiting …

///waiting …

>

Elpida laughed, or tried to. She was shaking. “Good. Yes. Now, I’m going to have to climb up into your turret and plug myself into your MMI uplink system, via that helmet up there. You grab Howl, stuff her back into my head. Right? Okay. So.” Elpida wet her lips. “Your main turret weapon, it’s for killing combat frames, isn’t it?”

>

///negative return no record

>

Elpida grinned. She couldn’t help herself, patting the control console. “That’s not an accusation. I put some of this together from what Thirteen told me. It’s for felling large targets. That’s what the weapon system is for, even if you’ve never used it for that purpose. Do you know what it’s called? What it fires? Anything at all?”

>

///negative return no record

///armament identifier corrupt

>

“Right. You can’t run it without a pilot. You can’t aim or fire without pilot permissions. You can’t even access the controls without a pilot. I don’t know why the people who made you decided that. I’m going to climb up into your turret and plug myself in, then we’re going to turn around and head back toward that fight. We’re gonna scoop up Howl, then we’re going to back up Arcadia’s Rampart with fire support. Understood?”

>Request orders

“No. This is not an order. I can’t order you to do this, Pheiri, because this means I have to climb inside your mind. Do I have your consent, little brother?”

>Commander

The green text vanished. The screen went dark. Elpida felt Pheiri slew to one side, crashing through brick and rubble. He was turning back toward the fight.

Ooni wailed: “This is madness! It’s like a fight between gods! We can’t, we’re going to die! This is madness!”

Pira snapped, “Madness has worked for the Commander so far. Shut up. Close your eyes.”

“Leuca! Leuca, hold my— my hand, please— please—”

Elpida scrambled for the rear of the control cockpit, leaving Ooni and Pira behind. She slipped back into the connecting corridor and hurried to the turret ladder. The rungs were set too close together, built for somebody much more compact. Elpida hauled herself up the ladder and squeezed into the empty cavity inside the turret.

The space was tiny and cramped, full of equipment, all sunk in dark shadows and thick with dust. A bank of blank, broken screens blanketed the front of the turret compartment, perhaps once meant for showing external views. A curved seat was set into the rear, the stuffing long since eaten away or pulled out, leaving behind only a blank metal curve beneath the MMI uplink helmet.

Elpida threw herself into the seat. Her bare legs slapped against the cold metal. Her muddy, damp clothes stuck to her skin. She cut her hand on the exposed edge of the seat, but ignored the wound. She did not have time to care.

She yanked the MMI uplink helmet down.

The helmet was a simple steel-grey skull-cup, two inches thick, lined with conductive copper coils and patches of neuro-sensitive plastics. A cable emerged from the middle, as thick as Elpida’s thigh, leading up into a bracket on the ceiling and then down into Pheiri’s body. The cable ran all the way to his brain.

Elpida hesitated.

She had not yet processed what she had seen Thirteen and Arcadia’s Rampart change into. Pilots and combat frames, two equal seeds of something she had only dreamed of. Did that same potential lie within her? Or within Pheiri? He was based on combat frame technology, after all. His brain was Telokopolan machine-meat.

Would she feel some hitherto unexplored urge the moment she joined with his mind?

No, she decided. Pheiri had given no hint that he was unhappy within the secure shell of his own body. He had expressed nothing but the clarity of his current purpose. Perhaps the engineers of Afon Ddu had perfected something that Telokopolis had not — or could not. Pheiri was her little brother. She trusted his intentions and his Telokopolan heart.

Elpida raised the helmet. The cut on her hand smeared blood down one side.

“Here we go, Pheiri,” she said out loud, in case he needed the warning. “Keep those arms wide, be ready to catch Howl. Then, with the gun, I’ll handle the targeting, you just get us close.”

Elpida’s throat was thick with tension. Her heart was racing. Her hands were clammy.

What if she was wrong about Howl? What if Howl was not struggling against the current, desperate to return home? What if Howl was a traitor and a falsehood, a comforting lie, a Necromancer trick? What if Howl was not Howl?

Elpida cast aside all those what-ifs. They did not matter. If she was wrong, she was wrong. If Howl needed her, she had to be there.

“Time to be a pilot again. Hold on, Howl. I’m coming.”

Elpida pulled the helmet down over her skull. She felt a warm tingle, a flush of rushing thoughts, and a flowering of her mind into another.

Pheiri welcomed her home.

D-A-N-G-E-R C-L-O-S-E. That’s how we spell “fire support” in Afon Ddu.

Hooooo wow this chapter was almost kind of breather after the last few? This whole stretch of arc 9 has been very intense, with high drama and high action; we needed to dip back to Elpida for a bit to get our bearings. She’s doing better than expected, considering the circumstances, but once again she cannot resist the drive to plunge back into a fight to save her comrades and friends, even when that fight is vastly beyond her physical scale.

At least Pheiri’s got some big guns. Strap in and hold on tight.

If you want more Necroepilogos right away, there is a tier for it on my patreon:

Right now this only offers a single chapter ahead, about 4.5k words. Feel free to wait until there’s more story! I’m focusing on trying to push this ahead for now, seeing if I can make more time in my writing schedule to get an extra chapter or two out. I’ll keep doing my best!

There’s also a TopWebFiction entry! Voting makes the story go up in the rankings, which helps more people see it! This only takes a couple of seconds, and it really helps! Thank you!

And thank you so much for reading my little story! I hope you’re enjoying Necroepilogos, dear readers, because I am still having an absolute blast writing it. I still feel like I’ve barely scratched the surface of my plans for these characters and the details of the setting. There’s so much more to see. But first, a big fight! Until next week!